By guest contributor Ian Hansen

For those of us who are not financially invested in the expansion of war and the national security state, Fallujah’s siege by Al Qaeda does at least offer us a teaching moment.

The U.S. government, which says it is opposed to terrorism, is both manifesting terrorism in its policies and creating reactive terrorism among the people we pretend to be concerned with saving and protecting.

Reactive terrorism–often from groups with horrific oppression-supporting ideologies that are eerily reminiscent of the predominant militarism and dominionism in our own culture–allows our government to justify an even more extended campaign of terrorism that is both lucrative and sociopathically gratifying for a powerful subset of our ruling elite.

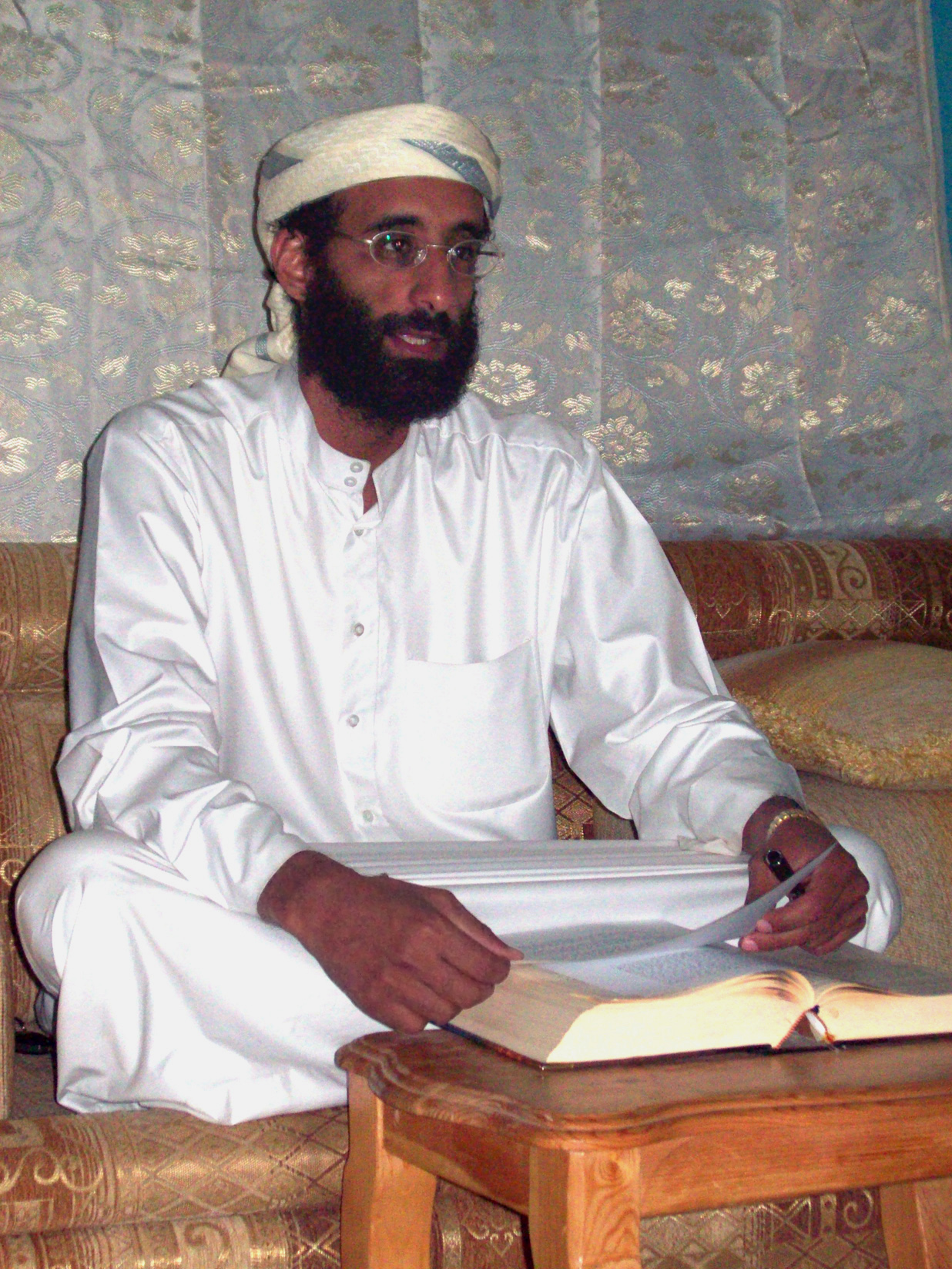

As we reflect on the fall of Fallujah to our enemies-like-us, we should reflect also on the violence-advocating and influential cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. Awlaki was once widely known as a “moderate,” even Bush-supporting, Muslim U.S. citizen, and his turn to an ideology of violent hatred was also a product of U.S. ham-handedness and indiscriminate brutality in the name of fighting terrorism.

In assassinating the person al-Awlaki turned into, and doing so without charge or transparent evidence of his involvement in any crime (other than hateful and irresponsible free speech and friendly associations with Al Qaeda propagandists and other figures), the U.S. has set ominous legal precedents that cannot now be easily undone.

With his assassination, that of U.S. citizen Samir Khan, as well as of Awlaki’s clearly noncombatant and unaffiliated 16 year old son, the U.S. has symbolically tainted its War on Terror with the blood of Absalom.

When we fight wars, we believe are fighting against some Other, but there is no Other. All acts of violence are ultimately carried out against oneself, because the chain is unbroken.

And since our government will not cry tears of remorse, we must be the ones to weep, “O my son Absalom–my son, my son Absalom…O Absalom, my son, my son!”

Ian Hansen, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences at York College, City University of New York. His research focuses in part on how witness for human rights and peace can transcend explicit political ideology. He is also on the Steering Committee for Psychologists for Social Responsibility.