Americans are expected to pledge allegiance to a flag that symbolizes “liberty and justice for all.” But, as one of our readers asked recently, “What is justice?”

One common distinction is between retributive justice and restorative justice:

Retributive justice:

- Focuses on punishment for perceived transgressions

- Is imposed unilaterally on a weaker party by a stronger party

- Argues that the severity of the punishment should be proportional to the severity of the offense—e.g., an eye for an eye

- Is viewed as having a strong basis in Western values, particularly those of men

Restorative justice:

- Rejects the notion that punishment of an offender adequately restores justice

- Views transgressions as bilateral or multilateral conflicts involving perpetrators, victims, and their communities

- Recommends bringing together all parties to exchange stories and move toward apology and forgiveness.

Depending on our family and community values, we are exposed to varying levels of these forms of justice and develop ideas regarding which form is best. For example, in families:

- Authoritarian parents expect their children to be obedient and to follow strict rules and punish them if they don’t—consistent with retributive justice beliefs

- Authoritative parents are more democratic, more responsive to their children’s needs and questions, and favor understanding and forgiveness over punishment—consistent with restorative justice beliefs

And in nations:

- The U.S. incarcerates the largest number of people, including the most women in the world

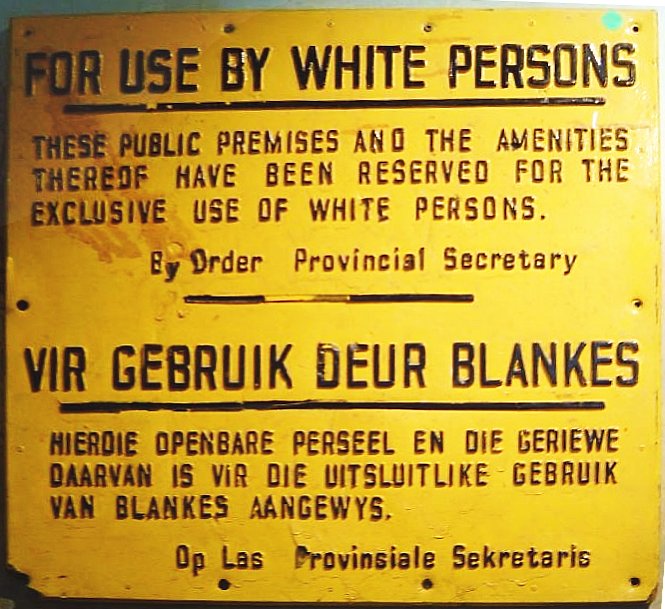

- Under Nelson Mandela, South Africa created a Truth and Reconciliation Commission “to enable South Africans to come to terms with their past on a morally accepted basis and to advance the cause of reconciliation.”

- The video above shows how the Rwandan government has approached the issue of justice in the aftermath of that country’s genocide

Which type of justice is embraced by each society? On what basis is one approach more just than the other? Which do you favor? Why?

Kathie Malley-Morrison, Professor of Psychology